Feature Stories | Mar 27 2007

By Greg Peel

In January, 2005 the spot price of uranium oxide hit US$20/lb. This is as high as the price had been since the early eighties. The highest it had been was about US$40/lb following the oil shocks of the seventies (about US$120/lb in today’s dollars), but the Chernobyl disaster of 1986 all but sealed the fate of nuclear energy on a meaningful scale – or so it seemed.

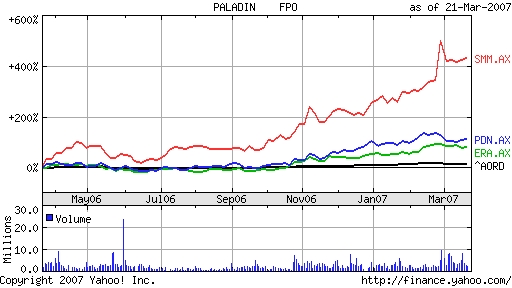

In January, 2005 the price of Energy Resources of Australia (ERA) hit $9.75. Two-thirds owned by Rio Tinto (RIO), and with long term contracts locked in at around the US$16/lb mark, stock analysts paid little attention. At the same time, another stock that was receiving little wide-scale attention was Paladin Resources (PDN), which hit $0.84 that January. Paladin had acquired the Langer Heinrich uranium mine in Namibia in 2002 for the princely sum of $15,000 (no typo).

But when the uranium price hit US$20/lb the penny began to drop for all but a handful of mining stock speculators with well-rewarded foresight. Because of wallowing spot prices and bad nuclear karma, the uranium industry had laid all but dormant for many years. Supply was limited, and it was provided as much from dismantling old Russian warheads as it was from out of the ground. But suddenly, demand had returned.

China was very much a spark in the demand equation, as it had been for just about every other commodity on the planet. Throw in growing global fears of climate change, and the scene was set. Given a glaring imbalance developing in the demand/supply equation, the uranium price could go higher still – much higher.

At the close of trade on March 22nd, 2006, the uranium spot price sat at US$91/lb – 355% higher than in January, 2005. The stock price of ERA was $25.22 – up 158%. The stock price of Paladin was $9.21 – up 996%.

As both companies can be considered “pure-play” uranium stocks, the disparity between each number appears curious. However, ERA, having produced uranium for many years was (angel) known in 2005 and (b) locked into long term contracts that meant it would not benefit from a surging stock price for years yet. Paladin was (angel) virtually unknown in 2005, and still two years away from its first production, and (b) able to sell uranium at spot. Macquarie analysts consider the enterprise value of both companies’ resource bases to be roughly equivalent (if ERA’s Jabiluka resource is not counted). Paladin simply needed to re-rate, and re-rate it did.

The only other Australian company producing uranium is BHP Billiton (BHP). As the world’s largest diversified miner, BHP’s uranium interest is lost amongst its base metal and bulk commodity interests. While BHP is sitting on the world’s biggest uranium deposit at Olympic Dam, production at the site is relatively poor. BHP has locked in its uranium sale price for years to come (ERA is just starting to improve its average), and it has even been forced to buy in uranium at spot recently to cover production short falls.

All other uranium interests in Australia are either foreign-owned, or not yet producing. Many are simply a plot of dirt with promise. If you wanted to be really cynical, you could note that neither BHP nor Rio Tinto (and thus ERA) are really exclusively Australian anymore, and that Paladin’s production comes from Africa. In other words, Australia does not have a uranium producer.

Yet a plethora of uranium or uranium-related stocks across the board have also taken off and surged in value since 2005. Let’s take a look at three, for the sake of argument: Summit Resources (SMM), prime source Queensland; Alliance Resources (AGS), prime source South Australia; and Nova Energy (NEL), prime source Western Australia.

Returning to our January 2005-to-now comparison, Nova (which actually listed in August, 2005, at $0.50) is up 596%, Summit is up 1908% and Alliance is up 4475%. Nice work if you can get it. Before our cut-off point, Western Australia was indicating there would never be a change to the uranium ban under the current government, Queensland was indicating the possibility of lifting its ban, and South Australia was already allowing uranium mining under a controlled licence-issue basis. The different stances are no doubt reflected in the different price movements, along with consideration of the total resources of each company.

Since this comparison cut-off, Queensland has indicated it would lift its ban in concert with the upcoming change in federal Labor policy. Premier Beattie needed to be convinced that uranium mining would not affect the local coal industry, and a commissioned report concluded just that. There was already, however, sufficient anticipation built into Queensland uranium stock prices. The stumbling block in WA is resistance to the “dumping” of waste in the state.

FNArena contacted each of these three example companies to get a handle on time-to-production. We learnt that Nova could commence production at its Lake-Way-Centipede site in WA within three-four years were a green light ever to be granted. Summit now has its green light and is targeting 2010 for its significant Valhalla/Skal project. Alliance has not yet received government approval for its part-owned Arkaroola, mine but suggests it is a two-three year start-up at best.

The important point here is that even with approval, these uranium projects will not be producing until at least 2010-11. Those companies sitting simply on promising test results rather than solid production opportunities are looking at a much larger time frame – at least five years and probably more. Apart from setting up mining and processing infrastructure, uranium companies must undergo bank feasibility studies (which banks won’t provide without mining approval) and extensive environmental scrutiny. The latter is far more extensive in uranium than for other commodities – no doubt a hangover from the old battles in the Northern Territory when Ranger was commissioned.

Another problem facing uranium miners is the increasing cost of equipment and staff. It’s hard enough to find mine-workers during the current commodities boom. Uranium experts are even thinner on the ground.

Uranium stock speculators have significantly re-rated a basket of Australian producers and hopefuls based on the uranium spot price move over the past year. That spot price move is a reflection of the real demand/supply imbalance existing at the moment, and of the need to secure supplies into the future. But it is a future spot price that will determine whether those miners looking at three or more years to reach production are over- or undervalued at present. While uranium supply contracts are secured for years in advance, there is no transparent futures market allowing the establishment of a reliable forward curve.

It all boils down to analysts’ estimates of the spot price of uranium in future years.

The Demand Side

There are two important points to note about a nuclear reactor. Firstly, it takes about eight to ten years to turn a proposal into a working reactor. Secondly, reactors consume a significant amount of enriched uranium in order to get the reaction started, but only a small amount to keep it going.

It is also important to note that while new reactors are being built or planned right across the world at present, older reactors are also scheduled to be decommissioned.

Analysts at Deutsche bank make the point that “the exercise of forecasting uranium demand is an exercise of forecasting when, where, and the size of new [reactor] builds over the outlook period, and forecasting when and where old reactors will be decommissioned. Both of these tasks are subject to a significant degree of uncertainty, primarily caused by volatile political situations”.

Nevertheless, Deutsche has concluded 89 new reactors will start up across the globe between now and 2015, and that 40 will close. Add in 442 current reactors, and the world should have 491 operating reactors by 2015. In settling on these numbers, the analysts did not consider reactors that were as yet mere proposals. Such reactors would not be up and running in the time frame.

Deutsche notes that the risks to the accuracy of such projections are a balance of the increasing recognition of nuclear power as an alternative to fossil fuels, and the setbacks that might occur in the case of another nuclear accident or if a rogue state became nuclear capable. In the case of the former, nuclear will improve its position as an alternative energy source if a global carbon credit trading scheme is introduced. Indeed, the recent report on a nuclear industry released in Australia noted that such an industry would be viable only if a carbon trading scheme was established first.

The world’s premier uranium producer, Cameco, suggests that by 2010, 10 new reactors will be coming on line for at least a 10 year period. Those ten reactors would require 2-3 years of inventory before commencing power generation, and would require 2-3 years to turn inventory into working fuel rods. This means uranium demand for 2010 could hit the market as early as 2007.

Nuclear power production is by far the most dominant use of enriched uranium. There are also medical applications and, of course, military applications, but they do not register on the scale and in the case of the latter, are not readily assessable. However, there is a growing new source of uranium demand – investors.

Uranium has not been overlooked in this century’s revolution in direct commodity investment. Like gold and other commodities, uranium now has a choice of exchange-traded funds to provide for investment funds to ride the uranium market directly. While official approval of ETFs has caused a level of resentment in other markets, such activity is particularly problematic in a tight uranium market. Sprott Securities estimates that Uranium Participation Corp and Nufcor Uranium have removed 5-7% of uranium supply from the market over the past two years. As the surging uranium price gains an even greater level of focus, it is likely that such funds will only gain in popularity.

The Supply Side

Uranium is abundant as copper. Yet copper trades at around US$3/lb and uranium looks like hitting US$100/lb fairly soon. One reason for the price difference is that uranium is only ever found around the world in very low grades, and hence an awful lot of earth has to be moved to recover it, but the main reason for the price differential is the age-old problem of underinvestment. For many years the uranium industry looked all but dead. Why would you have thrown money at it?

Since the great Chinese boom began in earnest, resource analysts have been incorrectly calling for a reversion to lower spot prices for most commodities given the historical cycle of supply catching up with demand. They have been forced to constantly shift out their catch-up assumptions into time due to a raft of problems besetting the resources industry, including production delays both man-made and force-of-nature, as well as strikes, cost overruns, scarcity of equipment and personnel etc. The uranium supply side is no different.

The supply scramble is now on, highlighted in Australia as one example by ERA expanding capacity at Ranger, BHP looking to triple capacity at Olympic Dam, and everybody else either rushing to get approval to exploit known deposits or madly trying to find more. There will be a noticeable increase in supply eventually, but as to when it will be able to catch up with demand any time soon is the point of conjecture.

Nor has the supply-side rush been aided by natural forces. Cameco’s massive Cigar Lake deposit was meant to be supplying 10% of global uranium demand by 2010, but due to flooding will now likely not even start production until 2010. ERA’s production at Ranger was set back by cyclonic rains. BHP has failed to meet production targets at Olympic Dam, resulting in the company being forced to buy in spot uranium to meet contract obligations.

Setbacks to major uranium mines play significantly on the uranium price because there are so few of them. In 2006, six mines accounted for 60% of production. Eight mines accounted for 70%. However, mines are not the only source of uranium.

36% of uranium supply in 2006 came from secondary sources. The two prime secondary sources are the reprocessing of spent fuel rods, and the decommissioning of nuclear warheads. Reprocessed uranium is rapidly becoming hard to find, and Russia – the largest source of ex-warhead, enriched uranium – has indicated it will stop exporting from 2008, although a supply agreement with the US extends to 2013.

Thus we have a uranium supply situation where there will be a tailing off of secondary supply either before, or around the same time as new supply comes on line. New supply is set to increase appreciably some time between now and 2015, but there is always a level of uncertainty. The greatest source of new uranium will be Kazakhstan, which represents 51% of proposed new mine supply.

Kazatomprom is Kazakhstan’s state-owned uranium producer and it has announced plans to increase production significantly from 2010. However, Kazakhstan suffers from a lack of infrastructure, and the same skills shortage as everywhere else. The Kazakh government also curiously insists that in situ mines must show a recovery level of 80% or better, and existing ones are currently struggling to reach that figure.

The Upshot

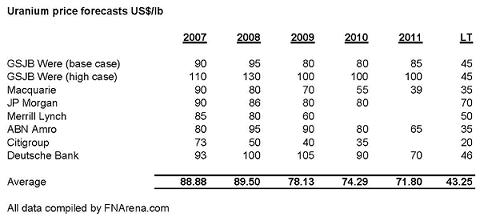

The following table represents recent uranium price updates made by leading stockbrokers.

The first thing that grabs one’s attention is just how low some of the forecasts are, given everything said above. Macquarie recently caused a stir amongst uranium stock speculators for pitching a long term price as low as US$35/lb, given spot prices are soon likely to exceed US$100/lb and few analysts expect supply to catch up with demand in the next few years.

One analyst who clearly indicates in his research a supply/demand deficit out to 2010 is Citigroup’s Alan Heap, yet a glance at his forecasts show they are wildly less than even Macquarie.

GSJB Were takes a bet each way, and thus pushes up the average with its “high case” scenario. But even this inclusion does not change the fact that the averages indicate a falling forward price despite general acceptance that supply is struggling and demand is rising.

To put these numbers into context, one has to appreciate three important points: (1) resource analysts have been understating commodity prices for the past three or more years; (2) commodity forward curves naturally decline on the assumption that higher spot prices attract new supply; and (3) long term prices always tend to historical averages. In the case of the latter, a small change in long term price can mean a very significant change in stock price valuation.

Nevertheless, the pervading belief evident in analyst reports is that the upside for uranium stock prices is not as spectacular as it was. Most analysts were slow to recognise uranium stocks on the move in the first place, and had to issue reports recently that had spot price forecasts and stock target prices leaping by large percentages. But now that everyone has focused on uranium, the positive mood is becoming less exuberant.

Of all the uranium stocks listed on the Australian stock market, only ERA and Paladin come in for any major stock analyst attention.

With ERA trading at around $26, the average 12-month target price in the FNArena database is $27.38. The high marker is JP Morgan at $31.00, and the low marker is Deutsche Bank at $20.31. There are three Buys and two Holds, with GSJB Were adding a long term Sell.

With Paladin trading at around $9, the average 12-month target price in the FNArena database is $9.98. The high marker is ABN Amro at $12.10, and the low marker is Macquarie at $8.40. There is one Buy and three Holds.

These numbers are not about to send ripples of excitement through the uranium investment community. They by no means imply, however, that the analysts have got it right. Analysts have been chasing up the price of zinc and zinc stocks for a long time, for example.

However, the uranium stock investor must now make a responsible decision on just how much euphoria is already built into prices – particularly small miners and explorers. What is going to change between now and 2010, for example, that is not already priced in? While uranium spot prices may easily exceed US$100/lb and more, and could do so for an extended period, isn’t this now accepted?

Canadian uranium expert Sprott Securities provided its analysts’ take on 2007 back in February:

“Unlike 2006 where the majority of uranium focused equities delivered triple digit returns, 2007 looks to be more about picking your spots for exposure to the commodity rather than investing in a basket of names. In 2006 the uranium price appreciated in excess of 90% now sitting at $75/lbs, and though we believe that the underlying fundamentals for the commodity will continue to drive the uranium through $100/lbs we do not anticipate the same level of equity appreciation to the group as a whole as we did last year. Investing in uranium in 2007 will be about picking your spots.

“The fury of the uranium equities has caused rampant appreciation for all levels: speculative to fundamental. We maintain that with the appreciation of the uranium price investors should remain focused on three subsets of uranium stocks; producers, imminent producers and those development stories with fundamentally solid assets aggressively moving towards production.”

In Australia’s case, “imminent producers” basically still means those with a good two-three year time horizon, as we established earlier. Based on analyst assumptions, these companies could potentially miss peak spot prices before being in a position to sign sales contracts.

Consolidation

But then there is the matter of industry consolidation. Anyone who has played the media market in Australia recently knows what sort of opportunities may exist when an industry is in a consolidation race.

The most recent local example is the bid for Summit Resources made by Paladin Resources. Despite Summit’s share price having rocketed in 2006, Paladin still effectively built a 35% premium into its bid. Although this sort of premium is usually what’s needed in a hostile takeover, it was simply a matter of Paladin being determined to gain full control of the Valhalla/Skal project.

Of course, Paladin’s is a scrip bid, so the company is leveraging off its own share price leap in order to achieve its objectives. It could not afford to pay cash.

But this doesn’t remove from the fact that uranium deposits are now well sought after, and that this means a lot of takeover activity potential, both locally and internationally. The largest deal to date has been last month’s friendly takeover of Canada’s UrAsia by compatriot SXR Uranium One to become the second biggest uranium producer in the world. UrAsia has most of its production potential in Kazakhstan, so the attraction is obvious.

What interested analysts was the implicit uranium resource valuation that emerged from the deal. UBS analysts calculated this figure to be US$31.61/lb. In other words, that’s the valuation put on UrAsia’s uranium deposits by SXR Uranium One.

Now all uranium mines will recover ore at different cost structures, but it is interesting to note that Australian companies tend to trade on a resource value of about US$16/lb, and that was up from US$9/lb last year. UBS noted that if the Canadian figure were to be applied locally, Paladin would be worth about $17 and ERA about $44. Add Jabiluka in for ERA and it would be worth $100.

This does not mean all Australian companies should yet again be spectacularly re-rated, but it does add food for thought when considering stock price upside.

Conclusion

There is probably not a lot of downside in uranium stocks in the next couple of years – that’s probably the safest conclusion one could draw at present, but that still does not account for the possibility that some highly re-rated explorers and fledgling developers may never see production. And those already producing will undoubtedly yet face the sort of production problems along the way that have dogged every mining company.

In terms of the safer bets, share price upside potential must be considered in the context of previous, spectacular moves, and just how long uranium prices will hold up at high levels vis-à-vis time to production. The overall outlook for uranium producers is bullish, but just how much of this excitement is already accounted for? Consolidation possibilities will probably provide some sort of floor.

Investors need to choose carefully, and choose well.