Feature Stories | Nov 23 2007

Why China Won’t Catch A Cold

Once upon a time when the US sneezed, the world caught a cold. But is that still the case today?

By Greg Peel

If Ebner and Gladys Luskowitz from Shoehorn, Philadelphia decide to stop buying things, then Japan, China, Asia, indeed the rest of the world, are in trouble. This is the fear being raised this past few months as the US stares down the barrel of a credit crunch-led recession. Even China’s Ministry of Commerce is now expressing its concerns. As the old adage goes: If the US sneezes, the world catches a cold.

From China’s perspective, the credit crunch could not have come at a worse time. It was over fifteen years ago that the US last found itself in such a situation, during the great Savings & Loans debacle. In the meantime, China has begun its process of industrialisation and rapid economic growth. It is now emerging as a world economic superpower. Why did the US have to choose now to blow it all on some dodgy mortgages? China was just starting to hit its straps.

But its all part of a circular argument. Americans have been profligate spenders, and have chosen to borrow money to acquire a bigger house, a bigger car and a bigger television rather than do what their parents did and save diligently for such luxuries. The entry of China into the global economy has provided a cheap workforce to which manufacturing can be outsourced. Thus the prices of durable household goods have fallen dramatically and brought them into the affordability range of many more Americans. But add in ridiculously cheap credit – a result of the US tech wreck and a decade of Japanese deflation – and Americans have found they can simply borrow to by the more expensive of these items. They have also borrowed to buy houses they can’t afford, because financial markets have forced credit upon them.

Thus the US had found itself deeper and deeper in debt. This was okay, for as much as Americans borrowed to buy imported goods the Chinese invested in US government debt as somewhere to park its excess foreign receipts. This symbiotic relationship has been one of mutual benefit.

At least until things started getting out of hand, and America’s current account deficit and China’s surplus equivalently ballooned. It’s not just China with whom the US has an offsetting deficit. Indeed balances against Japan and Germany are still greater. But the currencies of those countries float against the US dollar, allowing a rising cost of imports into the US to act as a dampening mechanism. The currency of China and other Asian countries, and many Middle Eastern oil-exporting countries, are, on the other hand, pegged to the US dollar. Hence as the US dollar falls it loses little purchasing power against those currencies. Import prices do not rise, and spending can continue unabated.

This relationship has been the cause of great consternation amongst economists across the world. The US-China imbalance is effectively a perpetual motion machine, without any of the friction of currency revaluation to slow it down. Economists suggest the Chinese renminbi should really be about 40% higher than it is against the US dollar on a purchasing power parity basis. If it was, then Americans would not be able to spend as much on imports and would need to rely on domestic producers for household goods. But it’s not, so America has relentlessly bought foreign goods at the expense of its own manufacturing economy. The less it buys locally, the more trouble its domestic economy finds itself in.

To fix the problem, China could simply let its currency float. But we have already come this far. To suddenly float the renminbi would be akin to suddenly making Tiger Woods tee off 100 metres further back than everyone else. Tiger would go from being the world’s most successful golfer to never winning a tournament again. Similarly China’s economic growth would go from 12% to not much and its whole emergence story would be derailed. What China has thus decided to do is make Tiger tee off one metre further back at each successive tournament. That way eventually equal competition will ultimately prevail, but in a calm and measured manner. China is revaluing the renminbi in tiny increments.

The US is rather frustrated with tiny increments, but not foolish enough to advocate an immediate float either. It is, after all, a symbiotic relationship. If China’s economic growth suddenly collapsed China would need to liquidate its foreign capital surplus, most of which is held in US Treasuries. That would be disastrous.

But now there is a new threat on the horizon. Imbalances aside, the US has found itself in a mortgage-led credit crunch which has infected the whole world. As housing values collapse, American consumers will potentially lose the will to spend, worried, as they are, that they will end up being unable to service their more expensive mortgages and have no equity value left in their homes to back them up. The American consumer represents 70% of the US economy. If the American consumer pulls the pin, the US economy will begin to recede.

America has started to sneeze.

Without the American consumer, the Chinese economy is staring into a hole. China’s is an export-dependent economy. The US economy represents 28% of the global economy. It may not require currency revaluation for China to face a hard landing. It may happen anyway.

If China’s economy suddenly slows then other world economies are also in trouble. China’s demand for the world’s resources will quickly diminish, and that would have serious ramifications for resource-rich economies such as Australia’s. A US recession will be devastating for the world.

Or will it?

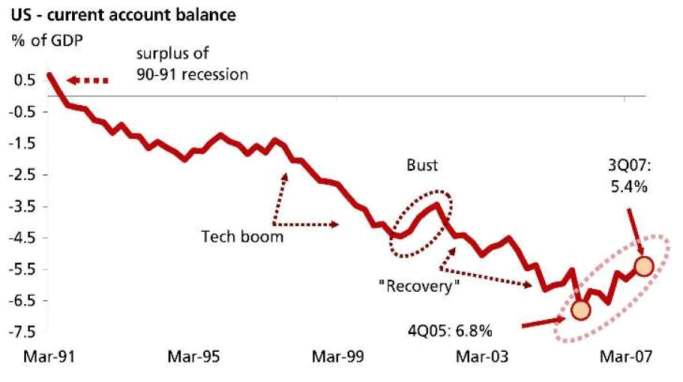

The reality is that the US current account deficit had stopped ballooning as a percentage of GDP and had begun to recede even before the credit crunch hit. The US dollar has been crashing against major currencies recently, but the previous trend had already been down – largely as a result of deficit concerns. When the US dollar falls, demand for imports from floating currency economies eases. At the same time, demand for US exports rises. It is the import/export (trade) balance that affects the bulk of the current account deficit.

While America’s traditional manufacturing economy may be dead in the water, with US union-negotiated wages and additional benefits (such as health cover) ensuring once dominant global companies like General Motors are struggling to compete, it is the non-traditional sectors of the US economy that have surged. No more is this as evident as in the technology sector, where companies like Microsoft (software), Apple (iPods), Research in Motion (Blackberries), Amazon (internet sales) and Google (search engine advertising) completely leave any competition – what there is – for dead. The US also dominates in other non-manufacturing based sectors such as pharmaceutical (drug development) and finance (unfortunately). We also know there is a McDonalds, a Starbucks and a Krispy-Kreme Donut outlet on just about every street corner in the world.

As the US dollar has fallen, US export demand has grown. If you don’t have an iPod now you’re just not a citizen of the twenty-first century, and it’s no longer a case of expense. The US may have outsourced its manufacturing to areas of low-cost labour, but the remaining “platform companies” still rake in all the profit margin from design and sales.

A country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a function of both domestic and foreign demand. DBS Group Research notes that in the June quarter, US GDP grew by 3.8%. But within this figure, domestic demand grew by only 2.5%. The balance was made up from foreign demand, which provided 36% of the growth. In the September quarter, foreign demand accounted for 25% of 3.9% GDP growth. Average the two quarters and you get 30%. In the previous two years, foreign demand averaged only 19% of GDP.

And despite China’s dependence on exports, the most foreign demand has ever contributed to GDP growth in China is 27% – in 1997. While China’s GDP growth has accelerated astronomically in recent years, the contribution from foreign demand in 2006 was only 20%. It is forecast to fall to an average of 16% in 2007.

DBS’s conclusion? China and the US are changing places.

The US current account deficit is falling. This is not because imports are falling, but because exports are rising. For all the concern over imbalances, the global economy is sorting itself out – without any disruptive intervention.

[Source: DBS Group Research]

But that does not detract from the fact that the US economy is still much, much larger than China’s. There must surely still be a risk that if the US goes into recession, China will suffer.

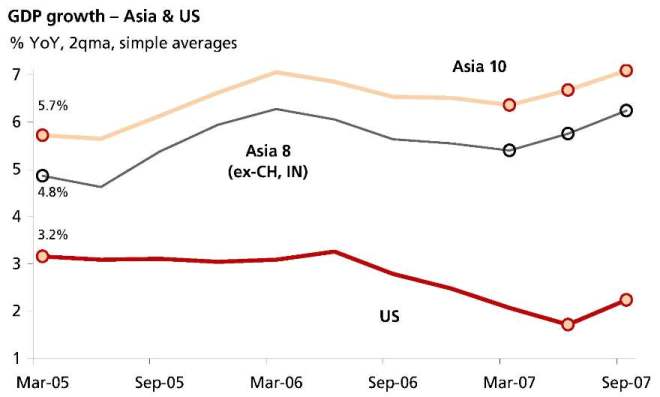

The US GDP growth figures for the June and September quarters quoted above are quarter-on-quarter figures. The reality is US economic growth year-on-year has been in an accelerated decline since the middle of 2006. (That’s declining positive growth, not the negative growth of a recession). If the sneeze/cold theory is actually still true, and the world’s fears are justified, China and the rest of Asia should have already been experiencing a decline in GDP growth since last year.

But a glance at the following chart shows the opposite.

[Source: DBS Group Research]

Note that this chart takes us only to September this year. Year-on-year US GDP growth registered 1.6% after the March quarter and 1.9% after the June quarter. It then registered 2.6% after the September quarter. In other words, there’s been a kick. If you look closely at the graph you’ll note the US growth rate began to slow shortly after Asian (ex-Japan) aggregate growth peaked in March 06. Asian growth then turned back up in March 07, and US growth turned up in June and September.

Is the US leading Asia, or is Asia leading the US?

Of course, notes DBS, the Asian economies are not yet big enough to drive US growth all by themselves. The US has also been propped up by Japan and Europe. The citizens of Tokyo, London and Berlin want iPods too.

What’s more, the peak of US year-on-year GDP growth actually occurred in mid-2004. US economic growth has been in decline ever since then. Since that time, US domestic demand growth has dropped by 2.8%, but foreign demand growth has dropped by only 1.8%. In other words, the US economy may be slowing but its fall is being cushioned by offsetting relative growth in foreign demand.

The US Federal Reserve this week lowered its forecast for 2008 US GDP growth by 0.5% to a range of 1.8-2.5%. This range is above the forecasts of many economists who believe US growth in the December and March quarters will at least drop to a range of 1.0-2.0%. Note that year-on-year US GDP growth registered 2.6% after September, so the Fed seems a lot more optimistic than everyone else. Particularly more optimistic than the real estate agents, home builders, car manufacturers and retailers of America, who have been crying out that the US is heading into recession, if it’s not already in one now.

But the reason economists are, for the most part, forecasting only a slowdown to 1-2% and not a recession is for the simple reason of the strength of the US foreign demand.

Now – there is a potentially circular argument here, because economists point to the strength of the global economy as being the crutch for the US economy even if domestic demand falls significantly. But then the argument goes that a slowdown in the overall US economy will, in turn, affect a slowdown in the global economy. Doesn’t that kick away the crutch?

DBS argues that far from being dangerously imbalanced, as many have argued the global economy to be, it is actually in the best state of balance it has been for 15 to 20 years.

In the late twentieth century, the Japanese economy was “dead in the water” and the European economy was “soporific”. Despite the fact the Asian economy had began to grow, it was still too small to make much of a difference. The US economy was absolutely and indefatigably dominant. But in the past few years the economies of Japan and Europe have been growing at around 2% per annum. Put these two economies together and their sum is 25% larger than the US economy. Thus if Japan, Europe and the US all grow by 2%, Japan and Europe are actually generating more in US dollar terms than the US. The economies of Asia (including China and India) are still only 38% of the size of the US economy, but at their current extraordinary rates of growth their actual growth contribution to the global economy will surpass that of the US in US dollar terms this year. Asia is no longer too small to make a difference.

In other words, the importance of the US economy to the rest of the world has never been lower. Says DBS:

“This is why the US current account deficit is falling. This is why Asia has been able to accelerate while the US has slowed. And this is why US income growth has suffered far less than it would have had the US been forced to lick its own wounds. The drivers of global growth are better balanced today than at any time in the past 15-20 years.”

Will Asia catch a cold if the US sneezes? Asian domestic demand is growing at a rapid pace. In another three years, DBS predicts, Asia will generate more incremental domestic demand growth than the US. And so it follows that while the Asian economy is still smaller than that of the US, in three year’s time Asia’s contribution to annual global GDP growth will exceed that of the US.

Perhaps we should really be worrying about Asia sneezing, and the US catching a cold.