FYI | Jul 06 2009

This story features RIO TINTO LIMITED, and other companies. For more info SHARE ANALYSIS: RIO

(This story was originally written and published on Wednesday, July 1, 2009. It has now been re-published to make it available to non-paying members at FNArena and readers elsewhere.)

It’s difficult to fathom, but true nevertheless, that China hardly figured on anyone’s radar as recently as six years ago. Today “China” is by far one of the most used references from investors and financial journalists alike. If it isn’t made in China, it’s probably caused by China, or bought by China, or financed by China. And if none of the previous scenarios apply, it is likely we’re talking about something that soon will be intertwined with China.

There’s an obvious flaw in all of this. Our day-to-day all-round usage of the term suggests China is one and the same all-encompassing entity, always truthful to one vision, loyal to one goal, adherent to one policy, always speaking with one voice while listening with the same two ears – no matter what the circumstances, and regardless of what is at stake.

That’s how China has gained itself a place in our psyche, yet we all know the concept is flawed.

In the world of natural resources, for instance, the term “China” covers so many different market participants, one could almost argue the label is more often wrong than correct. Apart from the central government and its desire to acquire hard assets, we have the people responsible for strategic reserves, then the state owned enterprises (SOEs), regional governments, private companies, commodity traders, intermediaries, producers, miners and explorers, financial speculators and investors – and that’s not counting foreign companies that have established a presence in the country.

To most of us, all of the above is covered by one single and simple term: China.

“China” is easy, but it also moulds our thinking. Ask any investor, analyst or commentator about what happened in energy and commodity markets this year and they will almost certainly respond with “China”. But who is China? It can be the central government, or the many entities it controls, but it can also be investors, traders and private companies that are anything but controlled by the central government (not to mention local authorities).

This is not just another hair-splitting, intellectual exercise. I am trying to explain why the general conception of what has happened in commodity markets this year is incomplete at best, and incorrect most of the time. And I am certain that by the last sentence of this story, your view on things will have changed.

It has been one of the major surprises since the near-global meltdown in late 2008: prices for commodities have doubled, or more than doubled, inside the space of a few months only. The explanation: “green shoots” signalling economic recovery and the return of investor confidence. Plus China, of course. China’s imports for the likes of aluminium, copper and oil have made up for the lack of demand elsewhere; plus some more.

How is this possible? Didn’t China’s exports dry up, its economic growth slumping to levels not seen for nearly two decades, while the country’s domestic demand is in its infancy at best? All this is true, though contested at first, but to counter the downward effects from the global economic downturn, the Chinese government has announced many trillions in government financed stimulus.

In the aftermath of the eye of the storm of what is globally known as the Global Financial Crisis, shortcut GFC, China is the only country that can do this.

Market commentators (not this one) who like to use the markets as a signal or as proof, have been advocating the noticeable uptick in Chinese demand for base materials as evidence the government stimulus is working. But none of the large number of large infrastructure projects that have been announced has effectively started yet.

So the explanation changed in that “China” has started to stockpile ahead of what will be an enormous task of getting all these large infrastructure projects off the ground and completed. A second reason soon followed: the central government had ordered the build-up of strategic reserves. The third one more or less fits in with the previous two: China’s desire to invest in alternative assets outside US Treasuries and bonds.

This is what most of us read in newspapers, hear on financial television and occasionally encounter in stockbroker research. This is the “China” that has saved miners and processors around the world from corporate failure, the one factor responsible for a sharp recovery in commodity prices while economic growth worldwide is still anaemic in most places.

This is, as one stockbroking analyst put it recently, why China has already imported as much in base materials over the first five months of 2009 as it was projected to do for the full calendar year.

It all makes sense, and it all seems but logical – until someone starts digging a bit deeper.

I am by no means suggesting that all of the above is incorrect, but the above picture is certainly not complete. What doesn’t stack up is the magnitude of China’s imports in 2009. To put it simply: the numbers are too high, reaching multiples of comparable data recorded in 2007 and 2008 – those were the peak years in the 2003-2007 commodities boom when China supposedly couldn’t get enough of anything it wanted.

So does all of the above warrant China importing and stockpiling two-three-four times as much as it consumed in the boom era years?

I don’t believe it does.

China didn’t just announce stimulus plans and introduce tax incentives, the central government also forced Chinese banks to significantly increase their lending. Again, the numbers that have been made public on this matter are simply gobsmacking. (It almost seems like China has already replaced the US as the country where everything is much bigger and larger than elsewhere).

The problem is, in an economy under downward pressure, private demand for debt (other than to replace old debt or to survive), is in decline too. This is normal, everyday economics. It happens in the US, in Europe, in Australia, and it does so too in China. In addition, Chinese banks have only just recovered from a grinding bad debts era, they didn’t exactly feel like stepping back in time.

The result?

A massive amount of new debt has been issued, well-exceeding the government’s targets, but predominantly to lower risk recipients. Many of those creditworthy businesses had no plans for expansion (demand for their products was shrinking), but they took the money nevertheless, courtesy of the “one favour for me, one favour for you” inner-circle business culture in China.

Where has all the money gone?

How about the share market? Chinese shares were among the first to recover from the bear market slaughter-fest.

How about the property market? Chinese property sales, prices and overall activity levels have bounced back, even though analysts have responded with surprise, or called it “probably too early to prove sustainable”. In addition, anecdotal evidence points into the direction of Chinese investors buying property in Australia too.

How about commodities?

As I have argued in previous analyses, it is but logical to assume large chunks of this idle liquidity have gone into the hoarding and stockpiling of base materials. With prices at a fraction of what they were at only a year ago, and with the prospects of Chinese stimulus, plus at least another decade of urbanisation and infrastructure upgrades in the country, and the assumption that sooner or later the rest of the world will get its act together again – what would you do with a million in the bank and no plans in particular?

I suspect the Chinese government is learning the art of capitalism the hard way. In this instance, the side-effects of its stimulative policies have not only created an army of overnight commodity speculators in the country, it has also badly backfired in that prices have run up much sooner and much further than would otherwise have been the case. This has not only impacted on the prices paid for the official inventory build-ups (also at regional levels), it has effectively cost the country its largest and most prestigious corporate deal to date: Rio Tinto ((RIO)).

Not to mention this year’s iron ore and coal negotiations.

All this, I hear you say, is but speculation and innuendo. I do not have any concrete evidence any of this is actually true. So be it. I am based in Sydney, Australia. But I notice other experts, some based in or with contacts inside China and Hong Kong, are increasingly looking into all of this, and drawing similar conclusions.

Former Morgan Stanley China expert, Andy Xie, is one of them. Xie is of the view that what we have seen in price rises for commodities this year is entirely the work of investors and speculators, both in and outside China. Real demand in China is not nearly high enough to support the size of imports -or prices- that have been recorded this year, Xie reports, without the slightest hesitation. Much of China’s 6 trillion renminbi credit boom since December has been channelled into asset markets, says Xie, not into productive economic projects or even tangible assets.

Xie points out Chinese banks have allowed loans structured for commodity purchases similar to mortgages; the underlying commodity (iron ore, coal, zinc) is used as collateral. In the same vein as my conclusion above, Xie states: “The global recession should have benefited China. Instead, the lending surge worsened China’s position by financing Chinese speculative demand”.

Xie suggests China’s bank lending splurge has turned ordinary businessmen into “de facto fund managers and speculators”.

Former hedge fund manager and current high profile global investment advisor, Frank Veneroso, has taken all of the above one giant leap further. Last week Veneroso reported he had obtained confirmation that Western hedge funds had joined Chinese speculators by entering the physical commodity markets inside the country.

Reports Veneroso: There are massive “hidden” stocks of copper in China and hedge funds are likely to be the largest owners of these hidden inventories. No surprise, his report often mentions the term “market manipulation”.

Nobody knows exactly what is going on inside China, nor in commodity markets in general. Available data have always been sketchy and painfully incomplete. The fact that overall momentum has switched to China has not improved transparancy, and that is putting it mildly. Although most experts (and media) will point to, and seek answers in, underlying market dynamics of supply and demand, too little weight is as a rule attributed to the growing impact from financial markets and financial investors (speculators) on commodity prices. Gold is not the only commodity whose price can rise and remain elevated for an extended time without support from its natural and industrial buyers. We’ve seen uranium in 2007 and copper and crude oil in 2008.

What makes anyone think this time is any different?

Probably the easiest trap to fall into is to use present volumes and price levels as some sort of justification of economic strength or underlying demand recovery.

And yes, it’s all caused and explained by the term “China”, but probably not the China you thought you knew.

With these thoughts I leave you all this week,

Till next week!

Your editor,

Rudi Filapek-Vandyck

(as always firmly supported by the Ab Fab team of Rob, Grahame, Greg, Chris, Andrew, George, Pat and Joyce)

P.S. I – Frank Veneroso is no stranger to criticism of investor-led commodity fads and manias. Over the years past he has been giving speeches and presentations, including to the World Bank (mentioned elsewhere as a client of his), centred around the themes of investors getting ahead of themselves, and the growing impact from hedge funds and other speculators, until we end up with potential market manipulation.

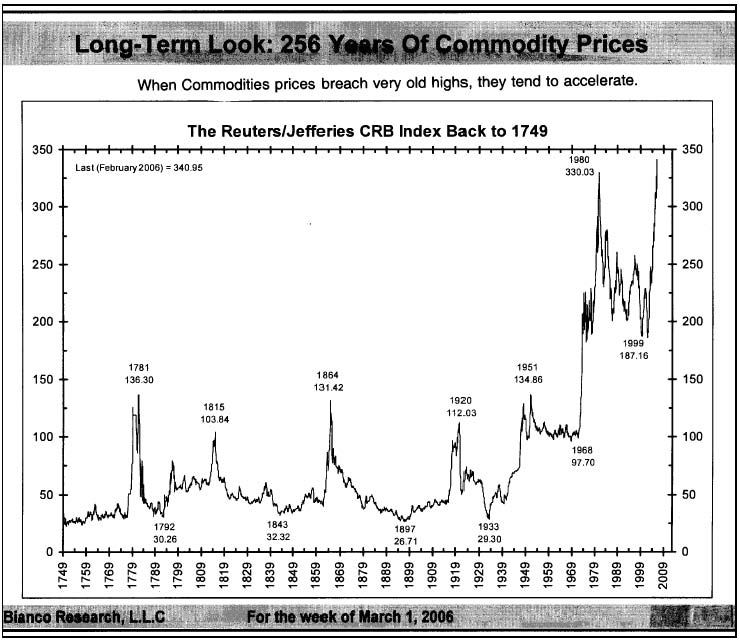

What makes the current Super Cycle for commodities so special, reports Veneroso, is that prices in absolute terms have run up so high without any sign of actual inflation. This is again the case in 2009. As early as 2007, Veneroso was talking about the “unprecedented commodity bubble”. In the absence of inflation, reports Veneroso, the present “bubble” is the largest we’ve ever witnessed in history (chart below) – don’t say thanks to China, say thanks to global liquidity, investment derivatives and to financial speculators.

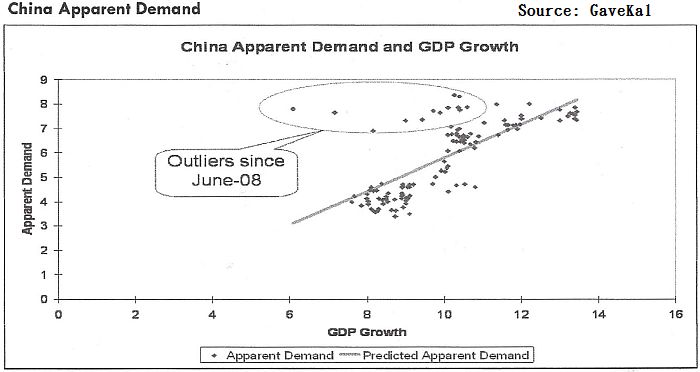

P.S. II – Long time oil bubble critics – the analysts at GaveKal – have repeatedly pointed out over the past year or so that underlying demand dynamics do not appear to be in synch with investor interest, or with the price of oil, for that matter. Last week, GaveKal published a chart (see below) showing the stable relationship between Chinese GDP growth and apparent oil demand has broken down since mid-2008. China building oil reserves? Yes sir. And there’s probably some more to it, too.

P.S. III – The matter has thus far received no airtime at all in Australia, but Chinese authorities have suggested the big three iron producers -Vale, Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton ((BHP))- have been importing iron into into the country to themselves, suggesting Chinese demand was inflated higher than it really was, not to mention this suggests the producers were artificially keeping pressure on Chinese negotiators during the annual price talks. I don’t think the Chinese can be completely trusted in this matter and certainly not under the present circumstances, but it’ll be interesting to see whether an investigation by the Chinese authorities will ever amount to anything.

P.S. IV – In my Weekly Insights from June 22 I used the apparent boom in coffee shops in my neighbourhood as an example of how investment boom and bust cycles work in financial markets. This week my favourite shop completely unexpectedly closed down. I couldn’t possibly have picked a more suitable end to the story: you just never know who’s going to win or lose, and when.

(If you are reading this through a third party distribution channel it is possible you won’t find the graphs and charts included. Our apology for this technical mis-match. Feel free to sign up for a free trial to our service and read the Real McCoy on the website).

Click to view our Glossary of Financial Terms

CHARTS

For more info SHARE ANALYSIS: BHP - BHP GROUP LIMITED

For more info SHARE ANALYSIS: RIO - RIO TINTO LIMITED