FYI | Oct 09 2006

Reader James Ward holds a Bachelor of Engineering (Civil) with Honours, and a Bachelor of Applied Science (Environmental Management), both from the University of South Australia. He is currently studying for a PhD in Hydrogeology at Flinders University, South Australia. He also convenes a peak oil discussion forum for young professionals on behalf of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil & Gas (ASPO-Australia).

James and FN Arena have been corresponding irregularly on the topic of peak oil over the past few months. Today we re-publish his written assessment on the topic of peak oil (with an amended quote attributed to ExxonMobil). James welcomes responses from other FN Arena readers. Please send all responses to info@fnarena.com (all responses will be forwarded to James Ward).

Crude Assumptions – The State of the Peak Oil Debate

Okay, so by now we’ve all probably heard about “peak oil” – the point at which the world reaches its all-time maximum oil production level and then begins declining, triggering a global economic/humanitarian crisis and proving once and for all that “limits to growth” are real.

Whether you think peak oil is a scientific reality or the wailings of a doomsday cult, as an idea it is very worrying and as a movement it is gathering momentum. It is generally accepted in the petroleum industry that production decline occurs after a given oilfield reaches its peak, and there are many places that have demonstrated that the phenomenon is also real on a regional scale. Countries such as the US, Norway, Venezuela and Australia have all reached their oil growth limits and production is now in net decline in those countries. Common sense then tells us that if all oilfields will eventually peak and then decline, there will inevitably come a point in time when the lost production from declining oilfields begins to outweigh new production from growing ones. That point is global peak oil.

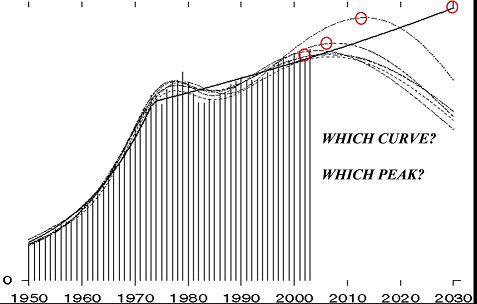

While the issue is truly compelling, it’s also a surprisingly difficult concept to get one’s head around. Some experts will tell you that global oil production can be simplified to a curve, and if we know the mathematical function to define what sort of curve it is, we can then predict when the peak will be. However, nobody can agree on what sort of curve it is supposed to be! Is it symmetrical or asymmetrical? Is it an early peak with gentle decline, or a late peak with steep decline? In fact there is a plethora of different mathematical curves that could be fitted to the historical production data with reasonable accuracy, and each curve predicts a different date and different height for the peak.

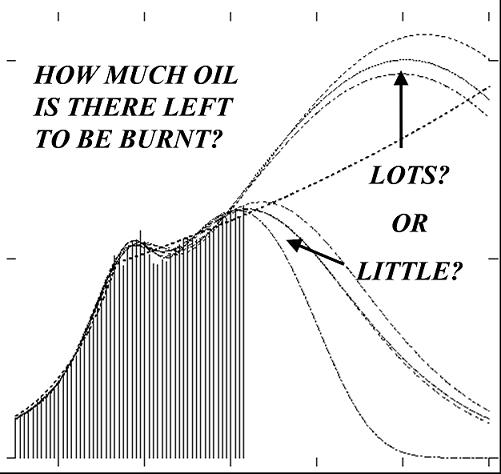

The other uncertainty is reserve size. Nobody seems to agree on how much oil there is left to be recovered. Are we half-way through our endowment of recoverable oil, or have we only used a quarter? Nobody really knows for sure because the volume of oil yet to be discovered, and potential bonus additions to existing fields, are both unknowns. This is really problematic if you are trying to decide whether to believe the peak oil pessimists or the oil company optimists. It would appear that a large amount of the common peak oil thesis relies on the assumption that we only have 1 trillion barrels left to be recovered, meaning statistically the peak should occur within the next 10 years.

But on the other hand, ExxonMobil has recently reassured us that there are 3 trillion barrels left (including non-conventional sources), and the peak is nowhere in sight. Mark Nolan (ExxonMobil) was quoting the US Geological Survey’s 50/50 bet that there might be 2 trillion barrels of conventional oil remaining that could be recovered, plus 1 trillion barrels of unconventional oil. At the moment the world’s drillers aren’t even on track to meet the USGS’s safest bet for discoveries (the one they were 95% certain we would exceed), let alone their higher estimates.

Now, if you delve into the depths of the debate, you discover a lesser-known method for predicting peak oil that does not rely on abstract mathematics or assumptions about remaining reserves. Chris Skrebowski, editor of the UK Energy Institute’s Petroleum Review and former sceptic of peak oil, has painstakingly assembled a database of regional oil production data from around the world. The database includes regions with growing production, regions that are in decline, and new projects coming online in the next few years. Furthermore, according to Skrebowski there is on average a 6-year lag between discovering new oil and that production flow coming online, meaning “any new projects that are to come into production by 2010/2011 would be known by now.” That means you can reliably predict production six years into the future based on what you know about today’s oil projects, but it also means you cannot extend the forecast beyond the six year outlook. In some ways, Skrebowski’s analysis is analogous to the headlights on a car: it doesn’t stretch very far ahead, but if there’s something there it will enable you to see it just before you hit it!

And the good news (if we put aside the whole issue of climate change) is that there are numerous new projects coming online in the next few years and global oil production can be expected to grow. The bad news is that according to all of the published production data and considering all these new projects, Skrebowski says decline will outweigh growth by the end of 2010. This is basically right in the middle of the range of dates predicted by the mathematical methods, and it is only a few years away.

There may be potential for increasing production from non-conventional sources of hydrocarbons such as coal-to-liquids, gas-to-liquids, heavy oil, tar sands, oil shale and methane hydrates. But as climate change is increasingly being recognised as one of the defining issues of our time, there is good reason for us to think twice before investing enormous sums of money in new, less clean ways to burn fossil fuels. And more importantly (in the peak oil debate, that is), the lag time for exploiting these non-conventional fuels is so great that none will come online (in sufficient volume) in time to offset the net decline due in 2010.

Skrebowski’s analysis is not the final word on peak oil – he has had to assume certain values for future growth and decline rates of the various regions. Skrebowski admits to the uncertainty and suggests the peak date could be as early as 2008, but is very unlikely to be later than 2010. In terms of uncertainty, his method is more robust than any method that depends on (a) guessing the recoverable reserve size, or (b) guessing the mathematical shape of the global production curve. And after all, at this stage, arguing about whether the peak will be 2008 or 2010 is a bit like shifting deck chairs on the Titanic to get the best view of the iceberg. The “take-home message” is that according to the most reliable data, and with the most robust analysis of that data, there appears to be no way the world as a whole will avoid a significant decline in energy production starting within the next 4 years and continuing for an unknown length of time – perhaps indefinitely.

James Ward holds a Bachelor of Engineering (Civil) with Honours, and a Bachelor of Applied Science (Environmental Management), both from the University of South Australia. He is currently studying for a PhD in Hydrogeology at Flinders University, South Australia.

Footnote: Thanks to Dr Marcel Schoppers for kindly allowing the use of the two graphs, which were taken from his presentation to the ASPO conference in 2005.